Brad Pitt won’t remember you. If you’ve met him, he’ll have no idea who you are when he meets you again. Even if you’ve had what he calls “a real conversation,” your face will start fading from his memory as soon as you walk away.

He’ll try to hold on to its outlines, but your features will suffer an inexorable erasure, and the next time he sees you you’ll be brand-new to him. He used to try tricking those he’d forgotten into thinking he remembered them, or at least waiting them out for a clue or scrap of context. But then he decided to experiment.

“So many people hate me because they think I’m disrespecting them,” he says. “So I swear to God, I took one year where I just said, This year, I’m just going to cop to it and say to people, ‘Okay, where did we meet?’ But it just got worse.

People were more offended. Every now and then, someone will give me context, and I’ll say, ‘Thank you for helping me.’ But I piss more people off. You get this thing, like, ‘You’re being egotistical. You’re being conceited.’ But it’s a mystery to me, man. I can’t grasp a face and yet I come from such a design/aesthetic point of view. I am going to get it tested.”

He is convinced he has that thing, that condition he read about a few years ago. What’s it called? Is he pronouncing it right? That’s it: prosopagnosia. It’s gotten to the point where he doesn’t even like going out — “that’s why I stay at home” — but he’s also a public person, the center of crowds. “You meet so many damned people,” he says. “And then you meet ’em again.”

And so, if you ever meet Brad Pitt, you should know a few things: He’ll probably forget you. He’ll probably worry about forgetting you. He’ll probably worry that you’ll think he’s an asshole for forgetting you. And then he’ll probably do or say something that will inspire you to tell people that you just met Brad Pitt, and he’s not an asshole at all.

“I like Brad because he’s not a cock,” the British director Guy Ritchie says. “He’s about as far away from being a cock as you can be. And it’s quite easy to be a cock in his position. It comes for free. If you’re famous and you’re good-looking, you have a license to be a cock. And I’m not sure if anyone has a bigger license than Brad. The license has ‘cock’ written all over it. And yet, he’s a good guy. That’s apparent and manifest as soon as you meet him.”

Ritchie met Pitt after he made Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels in 1998. Pitt did what he often does after he sees a movie he likes. “He called me,” Ritchie says, “and told me that he wanted to be part of whatever I was doing next.” They made Snatch two years later, with Pitt as a bare-knuckled boxer whose mumble made the lines he spoke incomprehensible. He was funny, as he always is in supporting roles, and he and Ritchie became friends. “He wasn’t a cock back then, either. I’ve never known him to be a cock.”

In the ensuing years, Pitt and Ritchie each took up with women of global fame and they each had kids, and when Pitt came to London last year to film World War Z, he took his children to play paintball with Ritchie’s children and impressed Ritchie with “his small army of rather efficient killers.

” Pitt is, in the estimation of Ritchie and indeed everyone who knows him, “a committed father.” He has also traveled a lot and seen a lot — “and those things can prevent cockery.” But let’s face it: “Every film ever made is about the temptation into cockery. Because that’s life. Brad’s temptations are greater than most people’s temptations, and for him not to act on those temptations means the challenges are greater. He’s in it every day. Is he not a cock by design? There has to be some degree of cognizance. A lack of cockery doesn’t just happen organically.”

It’s one of the great creation stories of modern Hollywood. Two credits shy of his journalism degree, with only one paper left to write before he graduated, Brad Pitt left the University of Missouri in his final semester and worked a couple weeks on the loading dock of his father’s trucking company in Springfield for gas money.

Then he got in the Datsun 200SX his father — “a big softie” — bought him and drove west. He had never been as far west as Colorado. He screamed as he crossed the Colorado state line and then at every state line thereafter, until he ended up in Los Angeles — “me and my big old mullet.”

He was already pretty good at leaving and not looking back, some kind of essential forgetting. Indeed, his only certainty was that he was not really leaving anything behind, because his life wasn’t back there in Springfield.

“I always knew I was going somewhere — going out. I just knew. I just knew. I just knew there were a lot more points of view out there. I wanted to see them. I wanted to hear them. I always liked film as a teaching tool — a way of getting exposed to ideas that had never been presented to me. It just wasn’t on the list of career options where I grew up. Then it occurred to me, literally two weeks before graduation: If the opportunity isn’t here, I’ll go to it. So simple. But it had never occurred to me. I’ll just go to it.”

He’s told this story before, but it’s worth telling again, if only because it’s never really ended. He was twenty-two when he left Missouri. He’s forty-nine now and, though almost as famous for being a family man as he is for being an actor, he still does most of his talking about arrival or about moving on.

Today it’s about arrival: He has just gotten back to L. A. after spending spring break at his home north of Santa Barbara and camping the night before with his partner, Angelina Jolie, along with their children and a few of their friends. He’s tired — “I woke up way too early and way too wet. But it was really fun. Six kids — six of ’em. Including one of our young ones. Angie as well. It’s a great thing, a great thing. Then we drove nine kids three hours in an Econovan.

The kind you take a crew in, with bench seats. No other vehicle is big enough. There’s no car we fit in as a family. Everything else holds seven, eight tops. An SUV only holds seven. And we had nine — our six and three friends. Eleven, including us. It’s no frills, man.

I’d love to have it all tricked out, shag carpet on all four walls. But we live in a different world. We rent our vehicles. We don’t want things so identifiable because we don’t want to get followed. We spend a lot of time trying to evade the paparazzi. It’s a big annoyance. But everything in life’s a trade-off….”

Pitt has arrived back in town for work, and he is speaking from a low leather chair on the first floor of a building devoted to postproduction on the Paramount lot. He is wearing a long-sleeved black jersey, dad-sized jeans of such stiff and unbroken denim that their creases form a jagged outline, and black motorcycle boots.

His hair, surfer-blond at the ends, is pulled into a short ponytail, and his whiskers, gray as an old dog’s muzzle, cover a face resolutely golden in color and grainy in texture. He’s wearing large sunglasses. When he takes them off, he reveals eyes that are blue and tired and wary, animated by alternating currents of curiosity and self-regard, and each bracketed by wrinkles that resemble a child’s drawing of the sun. He has a neck full of gold chains, tokens of his aesthetic alliance to the seventies.

He is bigger than you might think, and his ears are smaller, almost decorative. He is slightly pigeon-toed, with a rolling production of a walk suitable to a man who wears spurs. He has imposingly white teeth and a habit of sticking out his lower jaw when contemplating a question that makes him look as though he’s imitating Brando in The Godfather.

He has employed the same makeup artist for twenty-three years, Jean Black, and she applauds him for allowing his face to show its age, on- and off-camera, and indeed for using all the wear and tear as another kind of prop in his performances. “He’s not fighting it,” she says, and yet he is both rueful and amused that one of the things that attracted him to World War Z is that he didn’t have to work out for it — that he could play a hero without having to hang a six-pack.

In obeisance to the dictates of his family, he has not worked in a week. Upstairs, however, on the third floor, a half dozen or so people in the employ of his production company, Plan B, have been laboring to complete World War Z until they’ve turned pale as mine workers or, more to the point, zombies.

World War Z (out June 21) is Brad Pitt’s “zombie movie,” of course — a movie that he took on to see if he could make a movie that his sons could enjoy, a forthrightly commercial venture he hoped would serve as the foundation of his first commercial franchise.

Instead, it turned into a notoriously “troubled production,” fraught with reported cost overruns and creative differences. Pitt dismisses the notion that Z has been any more troubled than any other enormously troubled movie. He says that its notoriety came about “because of me — there’s a big bull’s-eye on my back.” What he does admit is that Z is a “big, big bet” for both Plan B and Paramount, “with a lot of money on the table,” and that he had a lot to learn about what it takes to make a big commercial movie.

“You gotta be able to make it pop,” he says. “You have to keep paying off, keep paying off, and in order to do that you have to be able to set the trap and snap it at the right moment. There are guys who are just great at that, and I didn’t understand how technically sharp you have to be to pull off some of that stuff.”

Pitt selected Marc Forster to direct the movie because he thought Forster would know how to keep building character even when his character is living up to his summertime obligation to kick some undead ass.

Pitt wound up spending a lot of time finding people who knew how to keep building tension while Forster was building character and, in Pitt’s words, “respected the rhythms” of action movies. He wound up being “more hands on” than he ever thought he would be, until World War Z was as much a Brad Pitt movie as it was a Marc Forster movie and belonged to him in a way no movie ever had.

Though its $200 million budget came from disparate and anxious sources, he owned it — and that turns out to be how he likes making movies and everything else.

He says he left Missouri because of “an itch,” and he says that the itch he felt then still guides him now. But what kind of itch is it, exactly? He makes movies. He makes wines. He makes furniture. He redesigns houses and works with an architectural firm to design apartment buildings and hotels.

He’s assembling whole neighborhoods in areas of abandonment and blight in three American cities and counting. He collects and races motorcycles. He has six kids. He’s engaged to one of the most beautiful and famous and demanding women in the world. Quietly and very slowly, as if trying to remember the words of a childhood prayer, he describes his life this way:

“I have very few friends. I have a handful of close friends and I have my family and I haven’t known life to be any happier. I’m making things. I just haven’t known life to be any happier.”

David Fincher has directed Brad Pitt in three movies: in 1995, Seven; in 1999, Fight Club; and in 2008, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. As such, he is privy to Pitt’s spasms of self-doubt: “Two weeks before he starts shooting any given project, Brad calls and says, ‘I’ve betrayed you. You have the wrong guy.

Here’s your opportunity to get rid of me now.’ Then he moves on. He’s not neurotic. He doesn’t second-guess himself. He just needs to get that out of his system.”

Fincher got to know Pitt before he was famous. “We’d meet at a diner or a Denny’s in Hollywood and nobody bothered us. Three weeks into Seven, we needed security. I’ve been in situations with Brad where we go out for pizza and he has sunglasses on and a beard and a scarf and a baseball cap, and seven minutes later we can’t go out the door.

All that was starting on Seven, and it wasn’t easy. There’s a madness that surrounds you. And you’re trying to navigate the world and to navigate your adult life, and there’s all these other things vying for your attention.”

Brad Pitt became a movie star before he had been able to make himself an actor. He knew it, and so did Fincher. What surprised Fincher, though, was how he responded. “In Seven, Brad was very anxious to go in and tear it up. He wasn’t all that comfortable, and it worked amazingly for what the character of Mills needed to be.”

Pitt’s secret, then, was simple enough: He wasn’t all that good. But he was already learning how to make his lack of experience and technique his secret weapon. Unlike some of his peers, he hadn’t been acting since he was a child and had never felt born to perform. He hadn’t had years of training; indeed, as he says, “my training is documented on film.”

“Before you are anybody,” Fincher says, “it’s hard to be yourself.” But Pitt had no choice. He had to learn how to be himself in front of the camera, because it wasn’t easy for him to turn himself into someone else.

He had to have a life offscreen if he wanted to make characters come to life onscreen and if, more to the point, he wanted to ask moviegoers to pay for the privilege of watching him. He already had fame, with its unrelenting artifice. Now he had to dive as deeply into it as a man could and find something like reality.

He does not call himself an actor. On forms, he lists his occupation as self-employed. “I learned that from Bruce Paltrow,” he says, referring to the father of his first famous girlfriend. “I always liked it. It’s a humble way to describe what we do.” And if a stranger on a plane were to ask what he does for a living, he would say, “Well, I’d be very Midwest about it, very Missouri. I’d say, This and that. I’d say, I’m a dad, just like you.“

His answer shows how hard he tries not to be an asshole and how hard it is for a person as famous as he is not to sound like one. In fact, he hesitates to identify himself as an actor not for reasons of humility.

He hesitates to identify himself as an actor because he considers himself primarily an artist, a doer, a maker, a craftsman, a man who felt the first thrill of artifice not onstage but in high school shop class, drawing up plans.

He hesitates to identify himself as an actor because he is forthrightly interested in leaving a legacy much larger than the legacy of his performances, which, however meaningful, are simply not as concrete as houses and chairs and wine or as endlessly real as children.

He likes the idea of being something more than an actor and he likes the idea of being something less than an actor, and when you tell him that you sometimes don’t look at him as an actor at all, he says, “That’s a great compliment. I appreciate that, as long as…”

“As long as…?”

“Well, some people say that because they see me as a celebrity. And then I’d go, Aaaaaaghhh…”

He is, of course, an actor. He is, of course, also a celebrity, which is what allows him to reach for a life beyond acting and what allows him to be occasionally mocked for his efforts. Indeed, his efforts to transcend acting — to transcend celebrity itself — are part of what makes him a celebrity in the first place, a member in good standing of the modern celebrity class.

Once about license, fame is now about virtue; once considered corrupting, it is now seen as civilizing or even ennobling, the charming reprobates of old replaced by enlightened global citizens. Brad Pitt is not the only movie star with a production company, a charitable foundation, or an interest in wine making; he is not the only one who turns up both on the cover of Us Weekly and in the poorest and most remote corners of the world; he is not the only one whose eye is exquisite and whose palate is cultivated; he is not the only one who works only with directors advancing the art of filmmaking and who leaves his most indelible imprints in supporting comic roles; he is not the only one who is fiercely protective of his privacy and devoted to a small coterie of longtime friends; he is not the only celebrity who hates being called a celebrity, as if the word itself puts at risk the very meaning he is so ardently and unironically seeking.

What makes him different from some of his peers, however, is not the grandeur of his ambition or the purity of his soul but a variation on what Guy Ritchie contends — the fact that when you meet him, he seems like a good guy, or, as his friend Catherine Keener puts it, “a fun hang.

” Whether or not he succeeds in his current enterprise of being human on a very large scale matters less than his success at being human on a small one. Take a look at the instantly parodied ad he made for Chanel No. 5. It seems the last word in privileged existential exhibitionism. It seems an indulgence on the part of a man who speaks of fame in terms of responsibility rather than freedom, when, in fact, it’s his freedom to be whoever he wants to be that makes him captivating.

His manager, Cynthia Pett, talks about the ad as an opportunity — an opportunity to be Chanel’s first male face, an opportunity to work with a director he admires, Joe Wright.

But none of that sticks, because we’ve heard it before. What sticks, instead, is her straightforward report on what her client said when Chanel came calling with what was reported to have been a $7 million offer:

“It’s the right moment and it’s a classic brand and I have six kids to put through college.”

He was the kind of guy who didn’t finish anything. You know that guy — you might be that guy yourself. “I’d get so far,” he says, “and then want to do something else. I mean, I’m two credits short of graduating college. Two credits.

All I had to do was write a paper. What kind of guy is that? That guy scares me — the guy who always leaves a little on his plate. For a long time, I thought I did too much damage — drug damage. I was a bit of a drifter.

A guy who felt he grew up in something of a vacuum and wanted to see things, wanted to be inspired. I followed that other thing. I spent years fucking off. But then I got burnt out and felt that I was wasting my opportunity. It was a conscious change. This was about a decade ago. It was an epiphany — a decision not to squander my opportunities. It was a feeling of get up. Because otherwise, what’s the point?”

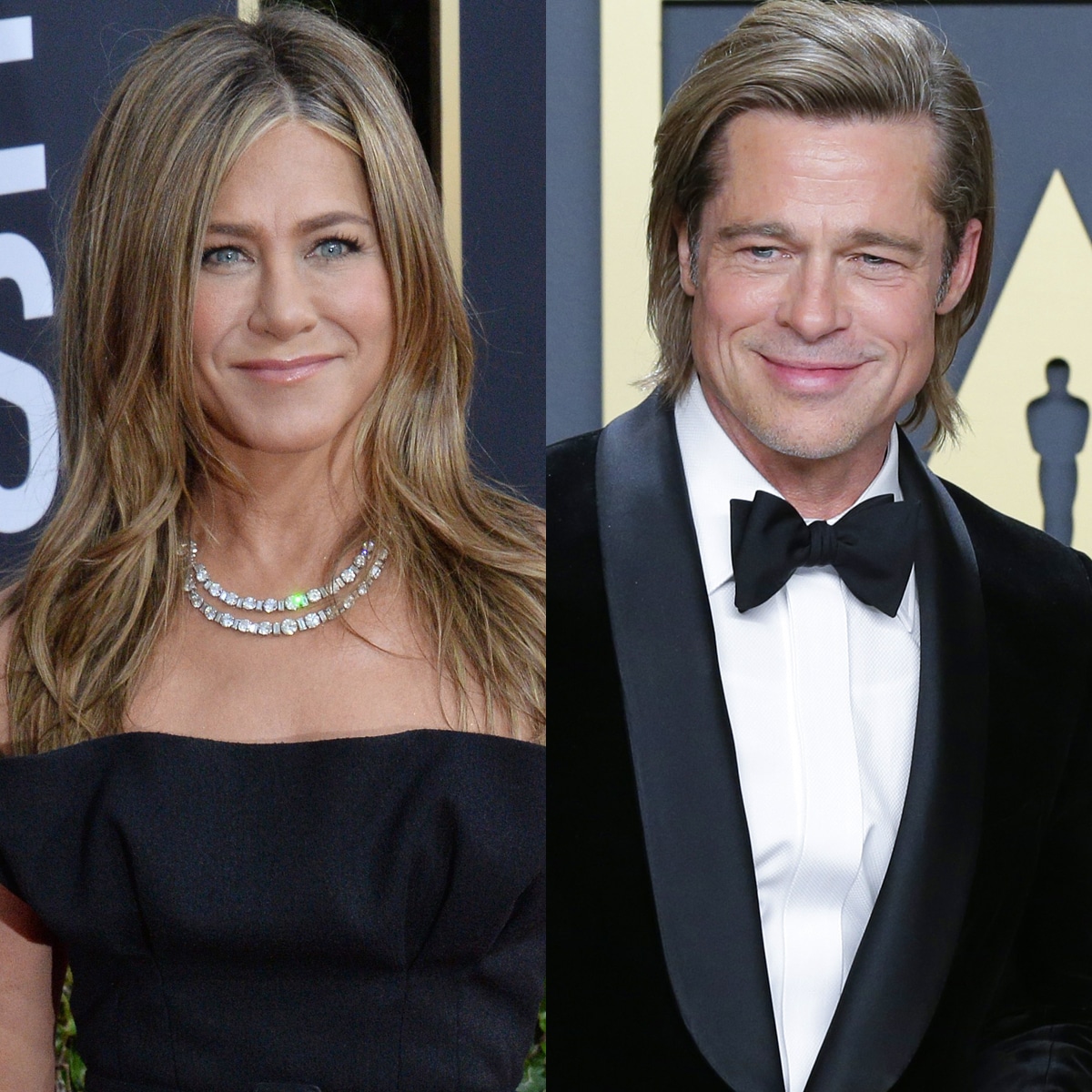

A decade ago he was still married to Jennifer Aniston. He had already changed himself, begun to change himself, when he made Mr. & Mrs. Smith with Angelina Jolie. Jolie, he says, “didn’t meet that person” — the one who left things undone.

“Now I finish,” he says. “It is very important to me to see things through.” In Jolie, he met someone who was wired not only to see things through but also to double down on the opportunities — for altruism and everything else—that her fame afforded.

“I think Brad was ready to soar when he met Angie,” says Jean Black, the makeup artist who has worked with him on almost every movie since Cool World in 1990. “This is not to say anything negative about Jennifer.

I was part of that and I know that he and Jen are very good friends and he cared deeply for her. But in Angie he saw a very adventurous person who was grabbing on to life and taking it to its nth degree. It was intriguing because I felt Brad had that in him and wanted to unleash it.”

Out of that also came both his family and his focus. “I always thought that if I wanted to do a family, I wanted to do it big,” he says. “I wanted there to be chaos in the house.” He does not mean instability.

He is the product of an intact Bible Belt household; Jolie the product of a broken L. A. one — and it is as if they’ve joined forces to produce the family that he remembered and she imagined. They’ve both turned out to be maximalists in that way, proud of all they’ve taken on, proud of their sheer numbers, proud of the daily disorder that vindicates their common dream.

“There’s a constant chatter in our house, whether it’s giggling or screaming or crying or banging. I love it. I love it. I love it. I hate it when they’re gone. I hate it. Maybe it’s nice to be in a hotel room for a day — ‘Oh, nice, I can finally read a paper.’ But then, by the next day, I miss that cacophony, all that life.”

They have three children by birth, three children by adoption, and together they constitute, in Pitt’s words, “one big mess.” It is in keeping with his nature not to distinguish between them.

“There’s a different quality in being able to love someone who is not yours,” says Eric Roth, an adoptive father who has been Pitt’s friend since writing the screenplay for Benjamin Button and who is the godfather of Pitt and Jolie’s nine-year-old son, Pax. “Brad has that quality in spades.

There is no differentiation between his attention and affection for those kids. They’re all part of his tribe; they’re like a moving caravan.”

The children are famous for traveling with their parents when their parents make movies, and the parents are famous for taking turns making movies so that one of them can be with the children while the other works.

The children are homeschooled and travel with their teachers. They have all, by Pitt’s estimation, been around the world three times. They have all, he says, “been thrown together,” which is what has bred, from happenstance, a bond based not on blood but on necessity.

“We suffer from a lack of privacy sometimes, but, on the other hand, we have to stick together. We are a little cut off from the herd, and so we have to look to each other for some kind of familiar experience.”

We, of course, have no idea what the actual experience of the family formed by Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie might be. We may assume — because they are, in fact, cut off from the herd, because they are so vulnerable and at the same time so protected, because they have been followed by strangers with cameras and sometimes feel hunted, because Pitt and Jolie are weirdly compounded in the public mind as “Brangelina,” because they have sold photos of their biological offspring to the tabloids for millions of dollars and then given the money to charity, because they live in compounds in L. A. and Santa Barbara and a château in the South of France — that the dynamics of their family life might be as exotic as their circumstances. But that’s why Pitt doesn’t like being called a celebrity.

When he left Missouri two credits short of graduation, his itch wasn’t for fame — it was for this, a life so large that it would feel indisputably real. He just had to find fame in order to get it.

He wakes up before anyone else in the house, without an alarm. The first thing he does: “I brush my teeth. And then I go and make the coffee.” He wears coveralls around the house and slip-on shoes. He cooks breakfast for his kids. He used to try to read the paper, but now he’s taken a year off from it. He does that — devotes himself to yearlong projects and quests.

He’s now learning to paint. He likes to build models with his sons and draw with his daughters. He collects vintage and custom-made furniture and has more motorcycles than he can count. He has bodyguards but not a publicist. He is the rare Hollywood star you wouldn’t want to fuck with. He didn’t get on a plane until he was twenty-five.

On his first trip to New York City, he squeezed into a subway car overcrowded with high school students and they pelted him with peanut shells. He used to smoke a lot of weed. He really likes pizza. He forgets faces but remembers everything you tell him. He’s not a cock. He likes to send Catherine Keener e-mails with ideas for band names.

When Jean Black sends him long e-mails, he sometimes writes back: “Huh?” He likes pranks, and once, on a private plane on the way back from the Toronto Film Festival, he drew a dick and balls on the face of his manager, Cynthia Pett, while she was asleep. With a Sharpie.

He goes to museums after hours and says, “It’s a lovely experience walking around a museum by yourself.” He once told his partner in the furniture business, Frank Pollaro, that he wanted to show him the design for a table, and when Pollaro came by his studio he saw forty different models of the table, all fabricated in wire.

He’s a perfectionist. He designed the hinges on the doors of the house in Los Angeles where he lives with his family. They are supposedly really nice hinges. It’s supposedly a really nice house, or compound of houses. “I never wanted to be rich until I met Brad,” says his friend, director Andrew Dominik.

“Because he knows what to do with it. You go to the homes of most movie stars and they’re like really, really nice hotel rooms. Brad lives in pieces of art. There’s a breeze blowing through every window. As soon as you walk through the door, you feel stoned.”

Bill and Jane Pitt still live in Springfield. Bill is, in his son’s description, “stout. Big hands. Big Popeye forearms kind of guy. He grew up doing. ‘You don’t get someone to fix your car, you fix it yourself’ — that kind of guy. He had to travel a lot when we were young.

He ran that trucking company, worked his way up from nothing. He worked hard to give his family more than he had — that kind of thinking is very much my dad. But then, at one point, he said, ‘I’m missing their childhoods’ and took another position in the company so he could spend more time with us. A lateral move. It was very much a conscious decision, so maybe that’s where I get that.”

Two years ago, Pitt portrayed a man close to the age his father was when Brad was growing up in Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. It is a film known for — notorious for — its far-flung metaphysical content, and Pitt’s portrayal of a man enraged by his stifled promise as an artist and ennobled by his volatile love for his three sons gave it whatever grounding it had.

Pitt’s character is locked in struggle with his sons because he tries to embody something he can’t articulate, and they hate him most when they inevitably disappoint him. He’s not a big softie. And although Pitt says that “my father could be very tough on us in matters of integrity,” he’s not supposed to be Bill Pitt, either.

“My father is a guy who calls to complain when people overcharge him for work on his house. He calls it ‘the celebrity tax.’ They think he makes what I make.”

Jean Black has met Bill Pitt. “Brad’s dad is definitely the powerhouse in that family. Jane’s this wonderful spirit and Bill is a man of few words, but when he talks you’re like, Uh huh. Conscious or not, Brad’s performance in Tree of Life was the reincarnation of his dad in that way.

And it was really difficult for him because he had to be very tough with those children. They weren’t actors. They’d never done anything like that, and so much of the movie was unscripted. Brad had to be mean to them, and that’s not the way he is with children. He made a point of doing things in between scenes to show how he felt about them.

“But they were terrified of him.”

A few years ago, he made a movie about being a celebrity. It was called The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. It was based on a novel by Ron Hansen. Andrew Dominik sent the novel to Pitt.

Pitt had contacted Dominik after his first movie, Chopper, and told him he wanted to work with him, but they had been looking for the right property. Pitt read Hansen’s novel in twenty-four hours and said, “Let’s do it.” Jesse James was from Missouri. He was famous. Pitt could play a famous guy from Missouri.

“The general thing with Brad,” Dominik says, “is that he’s Brad. He’s always Brad. If he plays someone who goes shopping at a supermarket, he has to act. Brad doesn’t go to the supermarket. He’s not an everyman, and that’s the reason he’s a star. You can dream on Brad.”

In Jesse James, he played someone who “was kind of tired and kind of a bad guy. Brad could do that. He has a sadness about him as a person, and I’m not sure where it comes from. And when he uses his skills as an actor, he can make you feel it. Brad’s a really mysterious guy.

I don’t know what he’s thinking most of the time. He has a very generous perspective on the world, and I don’t think it’s something he’s acquired because he’s had good fortune in life. Brad hasn’t become something from being famous. I think he was always that guy.”

He was not, however, a guy who spent a lot of time with other people on the set. “The whole family thing on a movie set — the bonding — is something Brad doesn’t do.

He walks away from stuff, and he doesn’t mourn it. But he’s not scared, and that’s unusual in Hollywood. You see, what’s going on in any movie is that the person with the most power is the star. He’s the one people worry about.

The studios worry about him; the executives worry about him. But a lot of people still want to stay out of sticky political situations, because they want to cover their own ass. Brad won’t. He’ll do a lot of heavy lifting, and he’ll use his muscle to go out and get what you want. He’ll just go out and do it.

I have a different situation. I’m an unknown entity. People expect to push you around, and unless someone comes to your defense you’re in for a very unpleasant time. Brad came to my defense even when he disagreed with me.

“So I consider Brad a friend. But I don’t go to his house and drink his beers and shit. There’s always a process involved if you want to see Brad.”

He still remembers the kid who made him not believe in God. “Grade school. He told me that when you meet the devil, you’re going to hear three knocks. And then the band would start playing — ‘Tubular Bells,’ from The Exorcist.

“Wigged me out. Because of the belief I was steeped in, the mythology I was living in, I stayed awake for three months waiting for the three knocks.

Then one night I heard them. I almost shit my pants. I thought I was done for. But the music didn’t play. Nothing happened. I still have a little beef about that. I still take issue with that — the loss of three months.”

He grew up among believers but was not a believer himself. His brother and his sister still live in Missouri and still believe.

They worry about him — the state of his soul. “We differ greatly on those beliefs, and yet I can’t change them and they can’t change me,” he says.

“But we’re family, man. We’ve always been family. We’re linked by blood and experience. I’m sure they’re saddened by me, and I get frustrated with them. But I love them, and at the end of the day if they need me or if they need anything, I’m there for them. Family.”

He is not superstitious. Because he considers religion an organized form of superstition, he considers superstition an individual form of religion — a weakness of mind writ small. “If I ever start to feel it, I go the other way,” he says. “I walk right under the ladder.”

He always surprises himself, then, when he prepares to travel apart from his family. “I get superstitious. I’ve always been that way.

I have to do a couple of things. I have to wear a couple of things. I have to have things with me. I’m not going to tell you what they are. But I’ve become that person when I do have to go by myself and leave the family behind. Because anything can happen, right?”

He plays that person in World War Z. Just as he plays a version of himself as a celebrity in Jesse James, he plays a version of himself as a father in Z — a man who has to leave his daughters in order to save the world. His daughters make him promise to come back and then to wear two bracelets so that he doesn’t forget.

He got that from life, as he got the song that’s part of the soundtrack. It’s an instrumental from Muse, and when he heard it he knew it was what he was looking for, because it sounded like “Tubular Bells,” and it scared the shit out of him.

He doesn’t scare easily. But World War Z is a compendium of the things that scare him. Having to leave his children. Music that sounds like “Tubular Bells.” A movie that cost $200 million. And crowds of people he doesn’t know.

Hell, World War Z is about crowds, and so when they were filming, he had to hire a thousand extras, and one hot day in Malta they were all packed in an alley, and he was in the middle of them. They reeked to high heaven, and by God so did he, a man wearing bracelets to help him remember, surrounded by a thousand hungry faces he would immediately forget.

News

Confirmados todos los rumores sobre Rocío Carrasco y Fidel Albiac: ‘Te lo juro’ (N)

Se confirma lo que está sucediendo en realidad entre la hija de Rocío Jurado y su marido Fidel Albiac Alba Carrillo comentaba este lunes en Mañaneros la presencia de su amiga Rocío Carrasco el pasado fin de semana en un evento en…

El chico que ha besado a Leonor en Brasil tiene un verdadero problema: ‘Hay más…’ (N)

Leonor le complica la vida a su nueva ilusión tras ser pillada dejándose llevar en los carnavales de Brasil Leonor sorprendió el pasado miércoles cuando fue pillada besándose con un misterioso joven en los carnavales de Brasil. Este hecho que…

Tensión en ‘TardeAR’ por lo ocurrido entre Verónica Dulanto y Jacobo Ostos (N)

En el plató de ‘TardeAR’ se ha vivido un momento de tensión por lo que ha sucedido entre Verónica Dulanto y Jacobo Ostos El programa de hoy de TardeAR ha estado marcado por la visita de Jacobo Ostos al plató y su presencia ha…

Carmen Borrego cruza los límites con Alexia Rivas en ‘GH Dúo’: ‘Ya no tienes…’ (N)

Carmen Borrego y Alexia Rivas protagonizan un increíble enfrentamiento en directo La última gala de GH Dúo estuvo marcada por la tensión y el enfrentamiento entre Carmen Borrego y Alexia Rivas. La controversia estalló cuando se anunció que José María Almoguera,…

Duelo de titanes en ‘GH DÚO’ tras la salvación de un nominado (N)

Ion Aramendi anuncia a un nuevo salvado de la expulsión más decisiva de esta edición de ‘GH DÚO’ ‘GH DÚO’ se enfrenta esta semana a una de sus nominaciones titánicas. La gala del jueves pasado, dedicada a San Valentín, dejaba una…

EL DRAMA DE ANABEL PANTOJA. “PIERDE 60.000 €”.(N)

El drama de Anabel Pantoja: “Pierde 60.000 €” Anabel Pantoja, una de las figuras más mediáticas del corazón español, ha vuelto a ser el centro de la atención tras la noticia de que ha perdido una importante suma de dinero….

End of content

No more pages to load