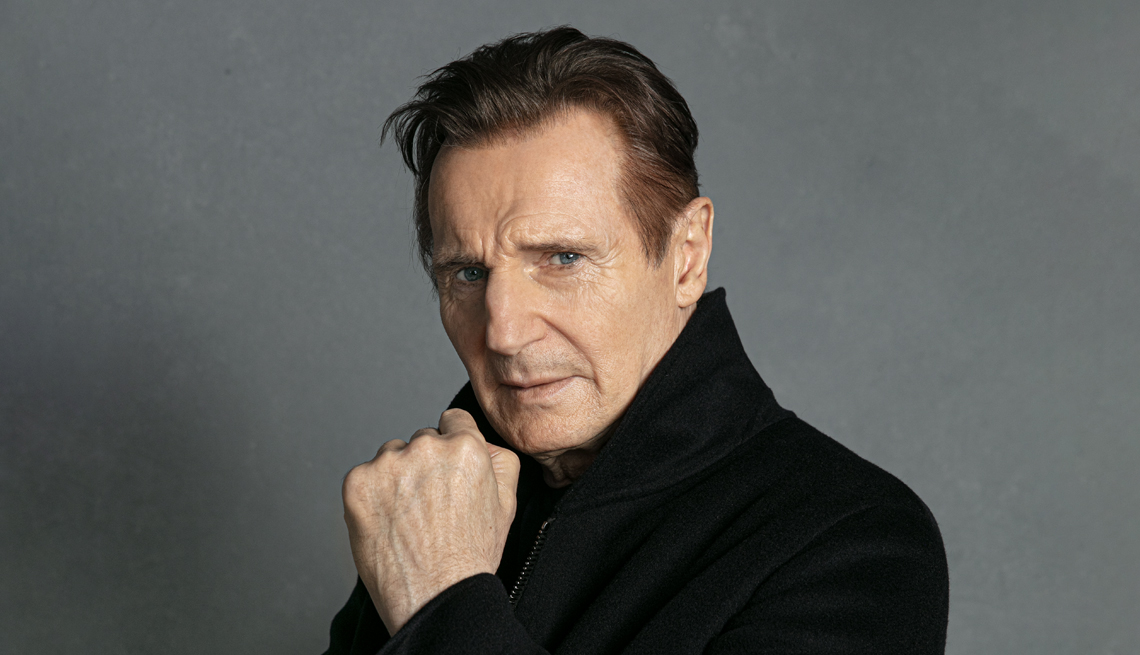

Whether he’s taking down Albanian thugs or big-city mayors, the soulful Irishman picks his fights (and his roles) with care. At 64, he still knows how to throw a punch.

Neeson carries this mug everywhere: movie sets, red-carpet premieres, New York Rangers games, even the occasional interview. “It’s a specific kind of English black tea,” he says when I ask what’s inside. “Decaf. It’s the only thing I drink.

” He’s not kidding: When the waitress comes over to take his order, Neeson reaches into his pocket and pulls out a Ziploc full of tea bags, which he unzips and hands to her. “Could you make me a fresh one of these, please?” Then he hooks a finger into the mug, fishes out the old tea bag, and drops it in his water glass with a plunk. “Thanks, love.”

Neeson folds himself into the leather booth as comfortably as is possible for a 6-foot-4 Irishman with shoulders like an armoire. He’s feeling a little out of sorts today: He has just finished shooting two movies back-to-back — one in Atlanta, the other in London — and he is in New York for the first time in five and a half months. “It’s nice to be home,” he says.

“But I’m feeling a bit like a three-legged stool.” (Which, technically, would be the most stable stool, but you get his drift.) He brings up one of the movies he’s here to promote — Silence, a historical epic directed by Martin Scorsese — and asks me how long it’s currently running. I tell him the version I saw was just over two and a half hours. Neeson shrugs. “For Martin, I guess that’s quite short.”

Silence is a passion project of Scorsese’s, one he’s been trying to make for more than 25 years. It’s based on a 1966 novel by Shusaku Endo about Jesuit missionaries — Neeson plays one named Ferreira — in 1640s Japan, where Christians are being systematically persecuted by the Buddhist dictatorship. The film has been through multiple writers and actors, but Scorsese stuck with it, and it’s finally hitting theaters this month.

Neeson understands the value of playing the long game. It’s a little hard to remember now that he’s entrenched on the A-list, but for most of his career he was a solid leading man, though rarely much more.

He was already 41, with 17 years’ worth of film roles behind him, when he was nominated for an Oscar for Schindler’s List, a role he’d reportedly beaten out Kevin Costner and Harrison Ford to get — but even that failed to give him Ford’s or Costner’s movie-star career.

Neeson spent the next two decades turning in great performances in as many hits as misses (Batman Begins on the one hand, The Haunting on the other), until his late-period pivot toward ass-kicking made him one of Hollywood’s most bankable stars.

“Liam’s ambition wasn’t to do all the classics at the Royal Shakespeare Company,” his old friend Richard Graham once said. “He wanted big parts in big movies.” Now, in the fifth decade of his career, he has his pick of them.

Neeson keeps his coat on for our entire time together, either as a sort of armor or in case he decides to make a quick getaway. He’s agreed to talk for 90 minutes, which I tell him isn’t long for an in-depth cover story. “Well it’s about 88 minutes more than I want to be here,” Neeson says. “So.”

That this rejoinder — delivered in his peaty growl — does not incite an immediate pants-shitting is due mostly to the fact that, intimidating though he may be, there’s an obvious gentleness to Neeson, a vulnerability and tenderness that’s plain on his handsome, timeworn face. Before he went around punching Albanians for a living, Neeson was usually cast in more introspective roles — professors, sculptors, and other sensitive types — wounded romantics who, like him, tended toward brooding and self-doubt.

Women, naturally, went crazy for him: the lumberjack’s body with the poet’s heart. “It’s not about looks, although he’s a terrific-looking guy,” his late wife, the actress Natasha Richardson, once said. “It comes from somewhere deeper than that. You feel that he’s been through a history.”

These days everyone knows that he has. Neeson is a widower, having lost Richardson seven years ago, following a skiing accident. Since then he has raised their two sons alone. Now the younger son is away at college and Neeson is home by himself. He still has his property in upstate New York, a big 1890s farmhouse he bought before he and Richardson were married. “He likes being there on his own, with his pool and his gym,” Graham says. “He’s always been very happy with his own company.

In many ways Neeson was born to play a priest. Tall, austere; slightly stooped yet unflaggingly upright; those searching eyes, that troubled soul. He’s done it half a dozen times already: in 1985’s Lamb (Brother Michael); 2005’s Breakfast on Pluto (Father Liam); 2002’s Gangs of New York (Priest Vallon, who wasn’t an actual priest but wore the collar and wielded a crucifix in battle); even an episode of The Simpsons, on which his Father Sean taught Bart the way of the Lord.

Neeson was born William John but called Liam (short for William) after the local priest. He grew up in Ballymena, Northern Ireland, the only son of Barney and Kitty Neeson, a school custodian and a school cook. His mother walked two miles to work each way and brought leftovers home to their council house; his father, according to Neeson’s sister, “never said five words when two words would do.”

Neeson learned the Mass in Latin as an altar boy: In nomine Patris, Dominus vobiscum, the whole deal. Church is where he first felt the magic of performance, the ceremony and theatricality of it — the robes, the candles, the liturgy; costumes, lighting, a script. His parish priest, Father Darragh, taught him to box when he was nine; a scrappy jabber with a strong left, Neeson eventually became the Ulster Province boys champion in three different weight divisions. But secretly he was afraid of getting hurt and, moreover, of hurting someone else. So when a blow to the head during a fight left him concussed, the 16-year-old hung up his gloves — but not before winning the fight.

It wasn’t easy being Catholic in Northern Ireland in the 1950s and ’60s. “You grew up cautious, let’s put it that way,” he says. “Our town was essentially Protestant, but there were a few Catholics on our street. The Protestants all had marches and bands and stuff. I didn’t quite understand what it was about — ‘Remember 1690? When Catholic King James was defeated by Protestant William of Orange?’ Who gives a fuck?” As he got older, the situation got grimmer. “The Troubles started in ’69 and then really kicked in from ’70 to ’71,” he says. “Drive-by shootings, bombs. I was at university for one abortive year, and we were so fucking naive. You’d be in a bar, drinking a glass of cider, and suddenly soldiers would come in and say, ‘Everybody out — there’s a bomb scare.’ We’d order more drinks to take across the street, then the soldiers would go off and we’d filter back into the bar. Fucking stupid.”

Neeson reconnected with his Catholic roots in 1985 when he filmed a movie called The Mission, starring Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons. The three of them played Catholic missionaries in 18th-century South America. They had a priest with them on set in the jungle, and every Sunday he’d “say a simple little Mass, break a piece of bread, and read the Gospel for the week,” Neeson says. “We’d discuss the passage and what it meant in today’s world. It was very intimate and very cathartic in a lot of ways.” A devilish grin: “Then you’d go home, have a few glasses of Guinness, and get laid. The delights of the flesh.”

Neeson’s part in The Mission was small but instrumental to his career. De Niro, whom he befriended, introduced him to an American casting director. When she needed an IRA operative for an episode of Miami Vice, she thought of Neeson. That got him a work visa and a foothold in the States.

He’s still grateful. “A lovely, lovely man,” Neeson says of De Niro. “He’s a man of few words — I like that. He’s the sort of guy who says, ‘I’ll call you Thursday at 3 o’clock’ — and if he can’t call, he’ll call you Wednesday to say he can’t. When he makes a commitment, he sticks to it. That’s rare these days.”

It was Neeson’s longtime interest in the Jesuits that prompted him to take the role of Father Ferreira in Silence. We first meet Ferreira in the film’s opening scene: He’s dirty, bearded, his raiments caked in mud — a thoroughly broken man. He’s forced to watch as Japanese Christians are crucified and tortured.

Neeson was eager for the chance to reunite with Scorsese, after the very brief experience working with him on Gangs of New York. “Martin demands real focus,” Neeson says admiringly. “If there was a grip working a hundred meters away and Martin heard a piece of scaffolding fall — which doesn’t even make a noise! — he would stop, turn to the first AD, and say, ‘I’ve asked for silence. Why have you not got it?’ Terrific.”

(Unlike just about anyone with even a tenuous connection to the legendary director, Neeson calls Scorsese by his full given name. “I just feel I haven’t earned the right to call him Marty.” he says. “Everybody’s always like, ‘Marty this, Marty that.’ You don’t know him. I don’t know him.”)

Scorsese says that Neeson was one of the key elements to finally getting Silence made. “I needed someone with real gravity to play Ferreira,” he says. “You have to feel the character’s pain.”

Now Neeson doesn’t consider himself much of a Catholic. “I admire people with true faith,” he says. “Like my mother, who’s 90 and gets annoyed if she can’t walk to Mass Sunday morning. ‘Mom, you’re 90! It’s OK! God will forgive you.’ ” These days he isn’t even sure if he believes in a God.

I ask if there was a specific incident that precipitated his doubt, and his face darkens. “So this is probably leading toward the death of my wife?”

Neeson is understandably wary on the subject of Richardson. It must be gut-wrenching to have to revisit the worst moment of your life again and again, every time an interviewer needs a new quote. But this was just an open-ended question, I insist. It wasn’t leading toward anything.

“OK,” he says, sounding unconvinced. “It wasn’t.” Anyway, as far as his waning faith goes: “I think it was gradual.”

When he’s in town and the weather is good, Neeson loves to walk around Central Park. “Power walk,” he says. “Get a good sweat going.” He even has a walking buddy — “a real-estate lady” he met on his walks. “You see the same people, you nod, you say hello,” Neeson explains. “Six months later, you’re saying, ‘How’s your kid?’ It’s nice,” he says. “We text each other: You free tomorrow? The usual spot? We do the whole loop — usually six miles, sometimes eight. Fifteen minutes a mile. It’s good.”

Three years ago, Central Park was the unlikely battleground for one of the most heated fights of Neeson’s public life. The topic? Horses. During his 2013 election campaign, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio vowed to enact a ban on horse-drawn carriages in Central Park. (The measure was billed as an animal-rights issue, though questions have been raised about the role political donors and real-estate interests played in the proposed ban, and Mayor de Blasio’s actions were later investigated.) The horse ban was supported by famous animal advocates like Miley Cyrus and Alec Baldwin. Neeson, who grew up caring for horses on his aunt’s farm in County Armagh, waded in to defend the drivers.

“I’m in the park every day,” he explains. “I see these guys; I know these guys. There were so many celebrities supporting [the ban], I was like, ‘These guys need a celebrity or two.’ ”

“He really put himself in the line of fire,” says Stephen Malone, a second-generation carriage driver and spokesman for the horse-and-carriage industry. “It was a complete game-changer. He hosted a stable visit for the city council on a Sunday afternoon, and if he wasn’t there, we might have gotten one or two [members]. We ended up with about 20. They got to take their selfies with Liam Neeson, but they also got to meet the children of the drivers and to see how the stable hands care for the horses. It completely swayed public opinion. That was the moment we knew we were gonna be OK.”

Colm McKeever, an Irish-born carriage driver and longtime friend of Neeson’s, says, “There’s a framed picture of him in every stable. It’s the Pope and then Liam Neeson.” McKeever says Neeson’s support of the drivers wasn’t due to their friendship: “We’ve been fast friends for a number of years, but that has nothing to do with Liam’s convictions. He stands up for what he believes in. It’s as simple as that.”

The proposal was eventually defeated, and now Neeson is a hero to the 300-odd drivers, who often stop him to say thanks. “It’s almost like he’s part of the tour,” jokes McKeever. “ ’There’s the carousel — and that’s Liam Neeson.’ ” Malone adds: “Liam Neeson is the biggest Hollywood star going right now, and he walks through Central Park and stops to talk to carriage guys. Only a true gentleman would do that.”

It’s a working-man’s solidarity that’s apparently characteristically Neeson. “If you speak to film crews, they all love him,” says Richard Graham. “He’s got friends from crews he still corresponds with — and I’m not talking about higher-ups, just ordinary blokes. It sounds like I’m blowing smoke up his ass, but he truly is an honorable guy.”

Ellen Freund was the prop master on two Neeson films, Leap of Faith and Nell — the latter when Neeson and Richardson were still dating. “They had a lovely house with a chef,” Freund recalls, “and every weekend they would invite six members of the crew and cook this fantastic dinner, with beautiful wines. It was just the most lovely treat. It wasn’t just the upper echelons, either — a grip or an electrician, it didn’t matter.”

It was Freund who introduced Neeson to his favorite outdoor pastime: fly-fishing. They were shooting Nell on a lake and needed something for Neeson to do in his downtime; Freund had just come off A River Runs Through It, so she showed Neeson how to cast. He was hooked. “He just loved it,” she says. “Once we gave him the rod and set him up out there, he wouldn’t come off the lake. Every time you looked for him, he was down there practicing.”

“When he said he’d discovered fly-fishing,” says Graham, “my first thought was, ‘My God, that is the perfect hobby for you.’ It’s peaceful. It’s in nature. There’s a lot of skill. And the time goes by like you wouldn’t believe. So I think that’s kind of therapeutic. You’ve got nothing in your mind, other than trying to catch the fish.”

Neeson cites the kind of pastoral tranquility that will be familiar to anyone who’s heard an angler wax lyrical about the sport. “Eight times out of 10, I won’t catch anything,” he says. “The thrill for me is being on a river with my pouch and rod, and I know there’s a fish over there, or at least I think there is, so I’ll do five or six casts. That fly’s not working, take it off, put on another one, try again. Before you know it, three hours will have gone past.” It’s the opposite of relaxing. “You’re trying to outwit a fish that’s been around since the Triassic with a piece of yarn or your own hair, he says. “You’re working all the time — but it’s a different kind of work.”

Neeson and Graham have fished together all over the world: Patagonia, arctic Quebec, the Tomhannock Reservoir in upstate New York. “New Zealand, that’s the mecca,” Neeson says. “Big trout. Stunning. Some of these rivers, we’d take little choppers in, and you’re six feet over the rocks and you jump out. You’re thirsty, so you put your head in the river and drink, and it’s pure.” Neeson seems energized by the memory. “Fuck. I haven’t done a big trip in a long time,” he says. “I’m thinking of going to Brazil, up the Amazon. Heard they have big peacock bass. That’d be a trip.” He would also like to get back down to the Bahamas for bonefish. “The phantom of the shallows,” he says. “Silvery color. They turn a certain way and disappear. Hence ‘phantoms.’ But you need a guide, that’s the only trouble.” He’d rather go alone? “Yeah,” he says.

(Says Graham: “We can be fishing side by side, 50 feet apart, and not say a word to each other for hours.”)

I ask Neeson if he’s learned anything from fly-fishing that he’s been able to apply to his career or to the rest of his life. “Patience, I think,” he says. “Just taking your time. I remember in the early days, if I was casting and I missed, I’d be very quick to cast again. But trout stay where they are — they like the food to come to them. The fish isn’t going anywhere. Take your time.”

Neeson’s other new movie is A Monster Calls, a live-action tearjerker in which a CGI tree (the titular Monster) visits a boy whose mother is dying. Neeson plays the tree, a yew — “the most important of all the healing trees.” He’s ancient and massive, twice the size of a house, with gnarled roots, spiky branches, and a voice like a bottomless coal pit. The first time he shows up, he kicks down the boy’s house. It’s kind of terrifying. Still, you know the Monster is good, because he’s played by Liam Neeson.

It’s not surprising that Neeson makes a great tree, given that a noted Broadway critic once literally compared him to a sequoia. (He actually called him a “towering sequoia of sex.” It was a compliment.) He spent two weeks filming motion-capture in a special room with cameras surrounding him on every side. “What do they call it? Not the space. The volume,” he says with a little laugh. “Computer nerds.” The end product looks something like a woodsy Transformer — which, weirdly, makes sense, given that Transformers director Michael Bay has said that Neeson’s regal bearing was his inspiration for Optimus Prime. (“Really?” says Neeson. “That’s news to me.”)

A Monster Calls is structured on a series of visits from the Monster, in which he tells fairy tales to the boy to help him work through his grief. The stories are designed to divine meaning from a meaningless world — a world where, as the Monster says at one point, “Farmers’ daughters die for no reason.” It’s a movie, in other words, about death, loss, mourning, and the ways we help one another cope. And this, I warn Neeson, is when I’m leading toward the death of his wife.

Neeson met Richardson when he was a 40-year-old bachelor who’d already dated Julia Roberts, Helen Mirren, and Brooke Shields. In 1993 Richardson and Neeson co-starred in a play on Broadway, Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie, and then, before long, were a couple. Two years later they were married in the garden of their farmhouse, and the boys soon followed. Then, in 2009, Richardson was skiing near Montreal when she fell and hit her head. Everything seemed fine at first: “Oh, darling — I’ve taken a tumble in the snow” is what she told Neeson on the phone that night. But unbeknownst to the doctors, her brain was slowly bleeding. She fell into a coma and died the next day.

Since Richardson’s passing, Neeson’s grief has colored several of his onscreen characters, a number of which are dealing with some kind of tragic familial backstory. The similarity in A Monster Calls is awful and impossible to ignore: a beautiful young mother struck down before her time. And Neeson’s own sons were just 13 and 12 when Richardson died, about the same age as the boy in the movie. Did he think about that at all when preparing for the film?

“Yeah, I don’t want to go into that,” Neeson says politely but firmly. “It’s not fair to them. I’d rather not talk about my boys, other than that they’re doing well, college, all that stuff.”

By all appearances, the boys are thriving. Micheál, now 21, is an aspiring actor who appeared with Neeson in an LG Super Bowl commercial last year. And Daniel, 20, is a sophomore theater and digital-media production major. “There’s a saying,” says Neeson. “ ’You’re only as happy as your unhappiest child.’ And the kids are happier than I — so that’s a blessing.”

We’ve been talking for a while when Neeson realizes his tea has gone cold. He flags down the waitress. “Sorry, love,” he says. “Could you ask the kitchen for some boiling water when you have a second?”

“Boiling-hot water,” she says, nodding. “No problem.”

Neeson stops her. “But not hot,” he says. “If you could make it boil. Tell them it’s for me,” he adds. “Tell them I will come for them. I will find them. . . .”

Upon recognizing his famous Taken monologue, the waitress cracks ups. “Absolutely,” she says, skipping off. After she’s gone, I tease Neeson for shamelessly trotting out his shtick. He laughs: “Pathetic, isn’t it?”

When Neeson made the first Taken movie in 2009, he had low expectations. “ Straight to video is what I thought,” he says. No one is more amused than he that eight years later — after The Grey (Taken with wolves), Non-Stop (Taken on a plane), Run All Night (Taken at night), and, of course, Taken 2 and 3 — he’s still getting offered this kind of role. He’s even reached the point of self-parody, turning in comically self-aware, Neeson-esque cameos in a commercial for the role-playing game Clash of Clans (as vengeful gamer AngryNeeson52) and on Inside Amy Schumer, as a scarily intense funeral-home director whose motto is “I don’t bury cowards.”

But in a way, Neeson is just fulfilling an opportunity he first had more than two decades ago, when he was being courted to become the new James Bond in the mid-’90s. “I was being considered,” Neeson says. “I’m sure they were considering a bunch of other guys, too.” He says he would have loved to be 007, but Richardson said she wouldn’t marry him if he was. I ask why, and he smiles like it’s the most obvious thing in the world. “Women. Foreign countries. Halle Berry. It’s understandable.” Also, Schindler’s List had just come out. “She was like, ‘You’re going to ruin your career,’ ” Neeson says. “But it’s no big deal. It’s nice to be inquired after.”

Neeson sometimes feels a little embarrassed that he’s Social Security–eligible and still pretend-fighting for a living. “Maybe another year,” he says of his action-star shelf life. “The audiences let you know — you can sense them going, ‘Oh, come on.’ But by the way,” he hastens to add, “I’ve never felt fitter in my life.”

Neeson doesn’t box anymore. (“I’ll train — the bags and stuff. But I don’t spar. There’s always someone coming up to you like, ‘Hey, you’re that actor Lyle Nelson right?’ They want a chance to hurt you a little. ‘Guess who I beat up today? He’s a pussy.’ ”) But he proudly points out that he does all his own movie fights. I read him a quote from Steven Seagal — “Look at Liam Neeson. He can’t fight. He’s a great dramatic actor, a great guy. . . . Is he a great fighter? A great warrior? No” — and Neeson seems amused. “I don’t know how to answer that,” he says, smiling. “Am I an action guy? Not really. But I do know how to fight. So fuck him.”

One thing Neeson absolutely won’t do anymore is ride a motorcycle — ever since a horrifying crash in 2000 nearly killed him. “I’ve read a couple of scripts where the character’s on a motorbike, and I’m like, ‘Is this important to the script?’ ‘Yeah, it is.’ ‘OK, I’m not in.’ ”

I tell him about a recent spill I took on a bike, and he turns serious. “You have to watch yourself,” Neeson tells me. “Get it out of your system. Make a pact with your wife. And don’t cheat on it.”

Neeson has few vices left these days. He quit the Marlboro Lights years ago and gave up drinking a while back — first the Guinness, then the pinot noir — after he found himself partaking too much in the wake of Richardson’s death. He tries to keep busy lest he wallow. “I need to work,” he says. “I’m a working-class Irishman. I’m fucking lucky: A stranger gets in touch with my agent and says, ‘Could you send Liam Neeson a script?’ I’m still flattered by that. So I’ll keep doing it till the knees give up. It beats hiding in a basement in eastern Aleppo.”

(As Richardson once put it: “I think he probably, on some level — although he wouldn’t say it — wakes up every morning thinking, ‘Isn’t it great I’m not driving a forklift?’ ”)

Now that he’s back in New York, Neeson looks forward to lying low for a while. “Just recharge the batteries,” he says. “I don’t want to see the inside of an airplane.” He’ll take in some Broadway shows, catch up on all the programs on his Apple TV: Fargo, Ray Donovan, Breaking Bad. He’s also got a big stack of books he wants to tackle — two Ian McEwan novels and a box of classics he recently received as a gift, which included War and Peace and The Grapes o

News

“$60M Rich Director Refuses to Collaborate with Liam Neeson after Controversial Remarks about ‘Hunting Down a Black B**tard'”

Liam Neeson is a renowned Irish actor whose illustrious career has made a lasting impression on the Hollywood movie industry. Neeson has a wide range of box office successes, and his amazing performances have captured viewers all around the globe. Neeson’s…

“Heartbroken Liam Neeson Shares Gut-Wrenching Story of Whispering Love to Brain-Dead Wife Natasha Richardson: ‘Sweetie, You’re Not Coming Back from This'”

Irish actor Liam Neeson has starred in a number of box office hits. Some of his most recognizable performances can be seen in the movies Taken, Love Actually, Star Wars, Batman Begins, Taken, and Schindler’s List. He was awarded an Oscar for his…

“Liam Neeson Reflects on Romantic Involvement with Oscar-Winning ‘Shazam’ Star During Prime Years”

In yet another sad ending to a Hollywood love story, a recent revelation by a pair has warmed the hearts of many. Talking about his former girlfriend Helen Mirren, Liam Neeson, the well-known actor, has shown nothing but gratitude. Neeson’s…

Liam Neeson is “Ashamed” He Kept Lurking Near Pubs to Target Black Men: “So that I could kill him”

Liam Neeson has come under fire after candidly admitting that years ago, he walked the streets hunting for a black man to kill in misguided revenge. The actor says he is “ashamed” and learned a valuable lesson from the disturbing…

“The Turning Point: Liam Neeson’s Career Transformation Triggered by a Phone Call 15 Years Ago”

In the movie released at the end of August, Liam Neeson continues to play a familiar fighting action role, associated with his image on the big screen for the past 15 years, after the fateful phone call in ‘Taken’. ….

“Liam Neeson and Glenn Close Deliver Haunting Readings of Trump Indictments, Saving Audiences the Trouble”

A new podcast unpacks the specifics of Donald Trump’s charges, relying on the A-list actors to emphasize their gravity Liam Neeson and Glenn Close are using their award-winning voices to help Americans understand why former President Donald Trump is under criminal indictment. In a new…

End of content

No more pages to load

| HO

| HO

EXPLOTÁ SCALONI EN CONFERENCIA DE PRENSA

EXPLOTÁ SCALONI EN CONFERENCIA DE PRENSA ¡TRAS LA PREGUNTA POR MESSI Y YAMAL! | HO

¡TRAS LA PREGUNTA POR MESSI Y YAMAL! | HO